Adidas has failed in an attempt to broaden trademark protection for its famous three stripes image in the EU. The General Court of the EU (GC), in upholding an earlier decision of the EUIPO, has found that the company’s registered European trademark for “three parallel equidistant stripes of equal width applied to the product in whichever direction” is invalid. The GC held that the mark was not a pattern mark but an “ordinary figurative mark” and it was not relevant to take account of specific uses involving colours. Moreover, the GC found that Adidas failed to prove acquired distinctiveness throughout the EU.

Whilst Adidas may appeal the decision to the European Court of Justice, and although the company does own several other three stripe marks which will remain unaffected by this decision, this is undoubtedly a setback for the company. This case serves as a timely reminder to all clients to be wary of the type of evidence they submit to the EUIPO, regardless of how well-known the particular image is perceived to be.

Background

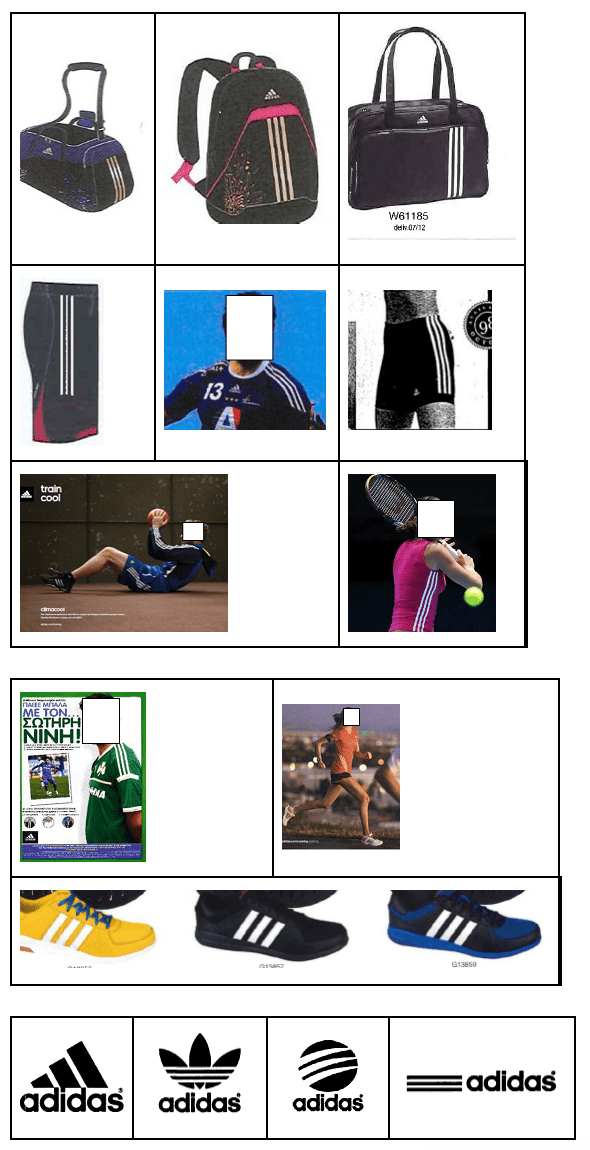

In 2014, the EUIPO registered, in favour of Adidas, the following EU trade mark for clothing, footwear and headgear:

Following a declaration of invalidity filed by the Belgian undertaking Shoe Branding Europe BVBA, the EUIPO cancelled the registration on the basis that it was devoid of any distinctive character, both inherent and acquired through use. According to the EUIPO, the mark should not have been registered. Adidas appealed and, whilst it did not dispute the inherent lack of distinctiveness, it submitted that its European Trade Mark had acquired distinctiveness through use. That appeal was rejected, and Adidas appealed again to the GC.

Figurative v pattern

Adidas argued that the EUIPO had misinterpreted the mark. It asserted that the mark represents a ‘surface pattern’ that may be reproduced in different dimensions and proportions depending on the goods on which it is applied. The company also argued that it constitutes a ‘pattern mark’.

The CG however, held that “Once a trademark is registered, the proprietor is not entitled to a broader protection than that afforded by that graphic representation” and that the mark at issue constitutes an ordinary figurative mark, as opposed to a pattern mark.

Permissible variations

Adidas criticised the EUIPO for having misinterpreted ‘the law of permissible variations’ i.e. the possibility of using variations of a mark in a manner which does not affect its distinctive character. On this matter, the EUIPO had found that:

- Where a trademark is simple, even a slight variation could lead to a significant alteration to the characteristics of the mark;

- The use of sloping stripes altered the distinctive character of the mark;

- Use of the mark in a form where the colour scheme is reversed alters the distinctive character of the mark; and

- Some of the evidence submitted by Adidas displayed a sign with 2 stripes as opposed to 3.

Ultimately, the GC agreed with the EUIPO that the following images related to signs which were not the same as the mark as filed:

Acquisition of distinctive character through use

Finally, Adidas claimed that it had provided a large body of evidence which should be assessed globally, regardless of the colour and length of the stripes shown and whether or not they were sloping. It also disagreed that the mark had not acquired distinctive character as a result of the use which had been made of it within the EU.

The GC found that the only ‘relevant’ evidence submitted by Adidas were 5 market surveys conducted in only 5 Member States. This was deemed insufficient to prove acquired distinctiveness throughout the EU.

Comment

Although the GC decision is a setback for Adidas, it is certainly not the end of their famous three stripes trademark. Adidas may appeal the decision to the European Court of Justice. Interestingly, the decision draws analogies with the difficulties recently faced by McDonalds in proving the distinctiveness of its BIG MAC European Trade Mark. Also, the lesson once again appears to be that regardless of the reputation enjoyed by a mark, clients should pay particular attention to the types and scope of evidence required to establish acquired distinctiveness through use in the EU.

To learn more about the impact of this judgment, contact a member of our Intellectual Property team.

The content of this article is provided for information purposes only and does not constitute legal or other advice.