Our Intellectual Property team examines a recent decision of the General Court of the European Union. The General Court found in favour of Glaxo Group Limited in a case concerning the invalidity of its trade mark for the colours lilac and deep purple when applied to the 3D shape of Glaxo’s inhaler. While the decision will now have to go back before the Board of Appeal, it is interesting for a number of reasons. In addition, they examine the implications for brand owners in the Life Sciences sector.

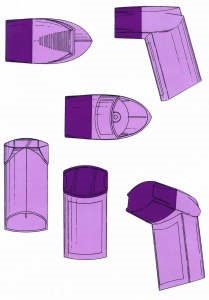

The never-ending battle for trade mark rights in particular shapes and colours for inhalers continues. This is illustrated by the recent EU General Court ruling in favour of Glaxo Group in a judgment relating to a European Union Trade Mark (EUTM) for the colours lilac and deep purple when applied to the 3D shape of Glaxo’s inhaler as depicted below:

We previously wrote about another similar case where Glaxo was unsuccessful here.

By way of background to the present proceedings, in 2014, an Indian based pharma company challenged the validity of the trade mark. A declaration of invalidity was granted by the Cancellation Division of the EUIPO. This was subsequently upheld by the Board of Appeal on the basis that the mark did not possess distinctive character.

This case also serves as a useful reminder that where there are individual elements of a trade mark which are devoid of distinctive character, when combined together they may in fact possess distinctive character depending on the overall perception of the trade mark by the relevant public.

In the case before the EU General Court, Glaxo challenged the decision on three grounds, two of which were successfully argued, and in particular, that more attention should have been given to the combination claimed. The appeal grounds were as follows:

Failure to examine inherent distinctive character arising from the combination of colour and shape

The General Court agreed with Glaxo’s claim that the Board of Appeal failed to carry out an overall assessment of the combination of elements of the trade mark even though it had examined the distinctive character of each element individually. The General Court found that although it was not necessary for the Board of Appeal to undertake a new detailed analysis of each item of evidence before it, it was nevertheless required to base its conclusion concerning the inherent distinctive character of the trade mark on an overall assessment of that mark. This is particularly so in light of the fact that the Board of Appeal gave different reasons for the finding that the mark was devoid of distinctive character.

The General Court also confirmed here that where the mark is a compound one, ie made up of different elements, just because each of the elements when considered separately are devoid of distinctive character, does not mean that their combination cannot present such character. The assessment of distinctive character must be based on the overall perception of the trade mark by the relevant public. In this case, the trade mark was made up of the inhaler shape, the colours ‘lilac’ and ‘deep purple’ and the particular arrangement of those colours.

Contradictory reasoning

Glaxo was also successful in arguing that the decision of the Board of Appeal was tainted by contradictory reasoning and this amounted to a failure to state reasons for its decision, which would be a procedural requirement.

By way of example, the General Court held that in the analysis of the inherent distinctive character of the contested mark, the Board of Appeal found, first, that the applicant for a declaration of invalidity had not demonstrated that the contested mark was devoid of distinctive character on the relevant date. However, subsequently and on the basis of the same evidence submitted by the applicant for a declaration of invalidity, the Board of Appeal came to the opposite conclusion. Here the Board of Appeal found that colours had, as far as concerns medicinal products for the treatment of asthma, a technical and informative function for consumers since they ‘show a certain reference’ to the active ingredients, their purpose and the characteristics of the medicinal product. The Board of Appeal found that such use of colours was descriptive. In light of this contradiction, the General Court found in favour of Glaxo on this point.

Failure to consider existence of distinctive character acquired through use

Glaxo was not successful in its claim that the Board of Appeal did not consider the alternative argument that the trade mark had acquired distinctive character through use. The General Court rejected this claim on the basis that, while the statement of reasons in the contested decision was somewhat brief on this particular topic, the Board of Appeal did in fact consider whether there was distinctive character acquired through use. As correctly found by the Board of Appeal, the mark could not have acquired distinctive character in advance of the filing date as it had not been used across all member states and the evidence put forward failed to demonstrate that distinctive character had been acquired between the date of registration and the date of the application for a declaration of invalidity.

Conclusion

This case represents a win for Glaxo following its previous losses in the UK and EU courts in similar cases. It also confirms that the distinctive character of compound trade marks must be assessed based on the overall perception of the trade mark by the relevant public and not on its individual elements alone.

Nevertheless, the case will still have to go back before the Board of Appeal where it will decide again while taking into account the judgment of the General Court. As such, the battle for trade mark protection for colours and shapes continues in a market where trade mark protection for particular colours is extremely valuable to the owners of such marks.

For more information on successfully protecting your organisation’s intellectual property rights, contact a member of our Intellectual Property team.

The content of this article is provided for information purposes only and does not constitute legal or other advice.