The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts has just lost a landmark case against Lynn Goldsmith, the celebrity photographer who holds the copyright in the Prince headshot that inspired the ‘Orange Prince’ portrait. The US Supreme Court found that the ‘Orange Prince’ could not avail of the fair use defence for copyright infringement. Gerard Kelly, Head of Intellectual Property, summarises the US court’s findings and how copyright law in Ireland differs.

Background

In 1981, an iconic headshot of the music artist Prince was captured by celebrity photographer, Lynn Goldsmith. Goldsmith granted a limited license for this photograph to Vanity Fair on a ‘one time’ only basis to be used as an ‘artist reference for an illustration’. In turn, Vanity Fair hired the artist Andy Warhol who created a purple silkscreen portrait of the Prince photo, along with other versions of the print known as the Prince Series. Following Prince’s death in 2016, Condé Nast, the parent company of Vanity Fair, inquired with the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (AWF) about reusing the purple Vanity Fair image for a special edition magazine in honour of the deceased rock star. On learning about the Prince Series, Condé Nast opted for a license from AWF to publish ‘Orange Prince’ instead.

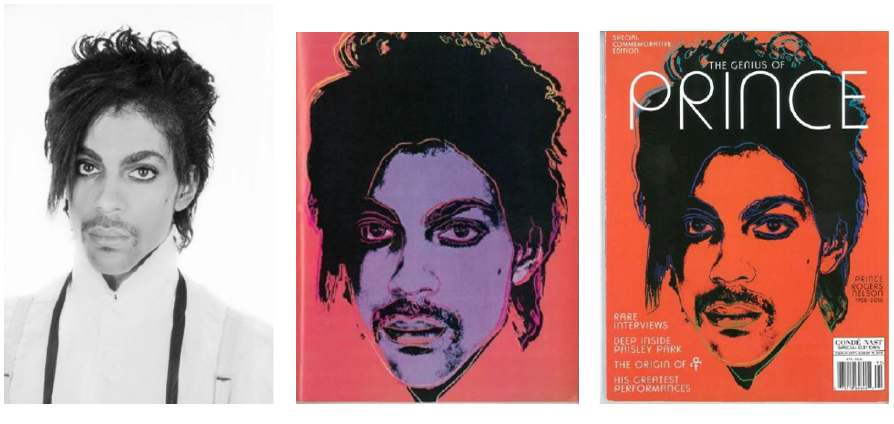

Goldsmith’s photograph (left), Andy Warhol’s purple portrait of Prince (centre), and the ‘Orange Prince’ on the cover of a magazine published by Condé Nast (right).

Goldsmith was unaware of the other prints that comprised the Prince Series until she saw the publication of the ‘Orange Prince’ on a magazine cover in 2016. She notified AWF that she believed her copyright had been infringed. AWF made the first move and sued Goldsmith, seeking from the courts a declaratory judgment of non-infringement or fair use. In turn, Goldsmith counter-claimed for infringement. Fair use is often raised in copyright cases when the alleged infringing use is arguably a non-competing derivation, such as where the original piece is used as a basis for pastiche, caricature, or parody. The matter was heard before a US District Court which considered the four fair use factors established under US law, namely;

- The purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for non-profit educational purposes

- The nature of the copyrighted work

- The amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole, and

- The effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work

The US District Court found in favour of AWF’s defence of fair use. However, the US Court of Appeals reversed this decision, finding that all four fair use factors favoured Goldsmith.

The matter was further appealed to the Supreme Court, where its sole consideration was in relation to the first fair use factor.

US Supreme Court decision

The US Supreme Court held that the ‘purpose and character’ of AWF’s use of Goldsmith’s photo did not fall in favour of allowing the fair use defence to succeed. AWF had argued that ‘Orange Prince’ was ‘transformative’ and conveyed a different meaning/message than the photograph. However, the court established that the first factor of fair use concerned whether there was a further purpose or different character attributed to the portrait and that the degree of difference between the two works needed to be weighed against other factors such as the commercialisation of that derivative work. The court found that the purpose of the derivative work was substantially the same as the original photograph; in that they both were used to depict Prince in magazine stories about Prince and as such, had a competing purpose.

The Supreme Court quoted US case law[1] in their analysis of the first fair use factor. They concluded that the first factor:

- Considers the reasons for, and nature of, the copier’s use of an original work

- Asks whether the use merely supersedes the objects of the original creation, or instead adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, and

- Asks ‘whether and to what extent’ the use at issue has a purpose or character different from the original

Most importantly, the court reiterated that the fact that a use is commercial as opposed to non-profit, is an additional element that must be considered when assessing the first fair use factor. The commercial nature of the use must be weighed against the degree to which the use has a further purpose or different character. To summarise, the court stated that ‘if an original work and secondary use share the same or highly similar purposes, and the secondary use is commercial, the first fair use factor is likely to weigh against fair use, absent some other justification for copying.’ As the commercial use was so similar to that which would be the typical use for the original photograph, a particularly ‘compelling’ justification for use was needed. Ultimately, the Supreme Court found that the first factor favoured Goldsmith and as a result, AWF lost its copyright battle against the celebrity photographer.

The law in Ireland

While this judgment is from the US and based on US law, it is up in the air how a similar scenario might play out in Ireland. The law in both countries is similar in that they both identify limitations on copyrights, such as in instances where the works are used for criticism, research, education, pastiche, etc. However, the Irish Copyright and Related Rights Act 2000 (as amended) does not explicitly provide for a fair use defence and doesn’t outline the factors to consider when assessing ‘fair dealing’. The only guiding provision under the Irish Act is the one which defines ‘fair dealing’ and states that the copyrighted work must be used for a purpose and to an extent which will ‘not unreasonably prejudice the interests of the owner’.

Back in 2013, the Copyright Review Committee released a report with suggestions for modernising copyright law in Ireland. This report suggested that ‘tightly-drafted and balanced exceptions for innovation and fair use’ should be introduced into legislation, and the Committee put forward a draft Bill suggesting amendments to the current Copyright Act. The draft Bill detailed 8 separate factors to be considered when assessing fair use, one of which is similar to the first fair use factor in the US. It considers ‘the purpose and character of the use in question, including in particular whether (i) it is incidental, non-commercial, non-consumptive, personal or transformative in nature…’ The Committee further opined that the exceptions for copyright infringement already provided for in the Act, should be regarded as mere examples of fair use, rather than an exhaustive list. This would allow for further fair use scenarios to arise under Irish law.

That being said, the draft Bill has not been implemented into Irish law. Therefore, the fair dealing defence under copyright law in Ireland continues to be a limited and more restricted regime than US fair use principles. As a result, in Ireland, there is less room for a defence argument around the use made by AWF above. Taking this into consideration, it is therefore at the Irish courts’ discretion whether they consider use to amount to being fair, and thus, an act permitted against works where copyright otherwise subsists; but it is likely the result would be the same in Ireland.

For more information on successfully protecting your organisation’s intellectual property rights, contact a member of our Intellectual Property team.

The content of this article is provided for information purposes only and does not constitute legal or other advice.

[1] Campbell v Acuff-Rose Music, Inc. 510 U.S. 569, 579

Share this: